By Rosalyn Jordan, BSN, MSc, RN, CWOCN, WCC

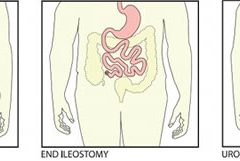

In most cases, amputation (removal of an extremity, digit, or other body part) is a surgical intervention performed to remove tissue affected by a disease and, in some cases, to provide pain relief. Fecal and urinary diversion surgeries also are considered amputations. Amputations and fecal or urinary diversions (ostomies) require extensive rehabilitation and adaptation to a new way of life, with physiologic and psychological impacts. Although diversions and ostomies usually are less visible to others than other types of amputations, they call for similar patient education, rehabilitatio n, and lifelong counseling.

The primary goal of therapy for ostomates and amputees is to resume their presurgical lifestyle to the greatest extent possible and to adapt to their new circumstances. Preoperative assessment and training interventions have proven valuable. Having a clear understanding of the surgical intervention helps reduce postoperative anxiety and depression, which can pose roadblocks to patients’ adaptation or response to their new situation. Successful interventions should be done by healthcare professionals who are trained in caring for ostomates and amputees.

Ostomates and amputees experience similar psychosocial challenges, body-

image problems, and sexuality concerns. This article focuses on these three issues. For a summary of other issues these patients may experience, see Other problems amputees and ostomates may face by clicking the PDF icon above.

Psychosocial challenges

Ostomates and amputees may experience depression, anxiety, fear, and many other concerns related to the surgical procedure—concerns that center on whether they’ll be able to resume their presurgical lifestyle. Many worry about social isolation and loss of income. Some fear both the primary disease process and the lifestyle changes induced by surgery. Anxiety may impede their social interactions and lead to significant psychological problems. Appropriate and effective counseling and therapy must be planned and provided. (But be aware that untrained or inexperienced healthcare professionals may not be able to provide the guidance the patient needs to feel comfortable; some may be unable even to offer information about available support systems.)

These patients also may find themselves socially isolated, in part due to loss of employment or the socioeconomic consequences of a decreased income. Some experience fear and worry when anticipating lifestyle changes caused by loss in or change of function, adaptation to the prosthesis, and treatment costs.

Maintaining social contact after surgery is extremely important to recovery and adaptation to the amputation or ostomy. The United Ostomy Associations of America and the Amputee Coalition encourage patients to maintain social involvement. Both groups suggest patients discuss their feelings, thoughts, and fears with a trusted family member, friend, or partner. Both organizations sponsor and encourage support-group involvement. In some cases, emotional support from other amputees or ostomates with a similar experience may be appropriate; some patients may be more comfortable sharing thoughts and asking questions in a group of people with similar experiences. Resuming presurgical social events and activities can enhance patients’ adaptation to a new way of life.

Help your patient find a support group at the website of the United Ostomy Associations of America: www.ostomy.org/supportgroups.shtml.

Body-image problems

Ostomates and amputees have to cope not only with changes in physical appearance but with how their body functions and how they feel and perceive their body. They’re keenly aware of their changed appearance and are concerned about others’ perceptions of them. They may feel anxious and depressed related to body image; the degree of anxiety and depression may relate directly to their presurgical body image and activities. Many become anxious and fearful as they adapt to the prosthesis. (See Stages of grief by clicking the PDF icon above.)

Compared to amputees, ostomates may have more concerns about body image with sexual partners, because the stoma is, in a sense, a hidden amputation. In most cases, the stoma and pouch can be obscured visually from others. The amputee, on the other hand, has fewer options for hiding the missing body part.

To help patients cope with body-image problems, care providers must offer education, therapy, and counseling to help the patient accept and successfully adapt to the body-image change. The first step in this process may simply be to have the patient look at the stoma or stump, progressing to participation in prosthesis care.

Sexuality concerns

Many ostomates and amputees have difficulty resuming sexual activity after surgery. Although the stoma usually remains hidden from others, it’s observable to the ostomate and sex partner. Most patients require an adjustment period before they feel comfortable with a sex partner. They may fear that:

• the partner will reject them or no longer find them attractive

• they will experience loss of function and sensation

• they will experience pain or injury of the stoma.

They also may feel embarrassed, causing them to avoid sex. However, counselors can help couples discuss these concerns and resume a satisfactory sexual relationship. Ostomates and amputees and their partners may need counseling to resume a satisfactory sexual relationship. If they continue to have adjustment difficulties, referral to a trained sex counselor or psychologist may be indicated. Several studies show that appropriate counseling can help prevent complications and allow amputees and ostomates to continue to express their affection physically. (See Talking to patients about sexual problems by clicking the PDF icon above.)

Resuming sexual activity may be easier if the ostomate or amputee had a sex partner before surgery. However, males who experience postsurgical erectile dysfunction are less likely than other males to resume sexual activity. Counseling encourages postsurgical patients to focus more on the pleasurable feelings they and their partners feel, rather than on sexual performance. Body-image problems and inadequate sexual adjustment go hand in hand. (See Helping ostomates resume sex by clicking the PDF icon above.)

Team approach to patient education and counseling

In many parts of the country, a designated healthcare team manages amputees’ care and rehabilitation. But until recently, nurses were the only professionals certified to participate in ostomates’ care and rehabilitation. In fact, ostomates may represent a significant underserved population. A 2012 study found many ostomy patients didn’t receive consistent training and counseling from ostomy certified nurses. Only 13% of respondents reported they had regular visits with an ostomy certified nurse; 32% said they’d never received care from an ostomy nurse. Just over half (56%) indicated they saw an ostomy nurse when they thought it was necessary. The study also reported that 57% hadn’t seen an ostomy certified nurse in more than 1 year.

A team with specialized training to address ostomates’ physical and psychosocial needs might be able to provide the specialized care these patients need. The primary medical caregiver or general practitioner would serve as team leader and make appropriate referrals. The team should include a surgeon, ostomy- and amputee-trained nurses, a prosthetist or other healthcare provider trained in selection and fitting of prosthetic equipment and devices that affect function, a physical therapist, an occupational therapist, a social worker, a vocational counselor, a psychologist, caregiver or family members, support groups, and (last but not least) the patient.

The team approach might reduce hospital stays and promote patients’ return to their home environment. It also might encourage independence and enhance the success of long-term adaptation.

Focus on the future

Healthcare providers should encourage ostomates and amputees to focus on the future, not the past. Feeling comfortable with the prosthesis—the amputee’s artificial limb or the ostomate’s pouching system—is essential to adapting to a “new normal” way of life. Maintaining social relationships is important to adaptation as well. Mastering basic skills and adapting to changes in body function help improve the patient’s quality of life. Follow-up visits, phone contact, and access to a team of well-trained healthcare providers for patient education, rehabilitation, and long-term management are crucial to these patients’ successful adaptation and quality of life.

Selected references

Bhuvaneswar CG, Epstein LA, Stern TA. Reactions to amputation: recognition and treatment. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;9(4):303-8.

Bishop M. Quality of life and psychosocial adaptation to chronic illness and acquired disability: a conceptual and theoretical synthesis. J Rehabil. 2005 Apr. www.thefreelibrary.com/Quality+of+life+and+psychosocial+adaptation+to+chronic+illness+and…-a0133317579. Accessed December 20, 2012.

Davidson T, Laberge M. Amputation. Gale Encyclopedia of Surgery: A Guide for Patients and Caregivers. 2004. www.encyclopedia.com/doc/1G2-3406200023.html. Accessed December 20, 2012.

Erwin-Toth P, Thompson SJ, Davis JS. Factors impacting the quality of life of people with an ostomy in North America: results from the Dialogue Study. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2012;39(4):417-22.

Houston S. Body image, relationships and sexuality after amputation. First Step: A Guide for Adapting to Limb Loss. 2005;4. www.amputee-coalition.org/

easyread/first_step_2005/altered_states-ez.html. Accessed December 20, 2012.

Maguire P, Parkes CM. Surgery and loss of body parts. BMJ. 1998;316(7137):1086-8.

Pittman J, Kozell K, Gray M. Should WOC nurses measure health-related quality of life in patients undergoing intestinal ostomy surgery? J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2009;36(3):254- 65.

Pittman J. Characteristics of the patient with an ostomy. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2011;38(3):271-9.

Racy JC. Psychological adaptation to amputation. In Bowker JH, Michael JW, ed. Atlas of Limb Prosthetics: Surgical, Prosthetic, and Rehabilitation Principles. 2nd ed. Rosemont, IL: American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons; 1998.

Tunn PU, Pomraenke D, Goerling U, Hohenberger P. Functional outcome after endoprosthetic limb-salvage therapy of primary bone tumours—a comparative analysis using the MSTS score, the TESS and the RNL index. Int Orthop. 2008;32(5):619-25.

Turnbull G. Intimacy After Ostomy Surgery Guide. United Ostomy Associations of America, Inc. Revised 2009. www.ostomy.org. Accessed December 20, 2012.

Turnbull G. Sexuality after ostomy surgery. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2006;52(3):14,16.

United Ostomy Associations of America, Inc. From US to YOU: living with an ostomy, the experience. http://www.ostomy.org/files/asg_resources/UOAA_Nursing_Information_Modules.pdf. Accessed December 20, 2012.

United Ostomy Associations of America, Inc. What is an ostomy? http://www.ostomy.org/ostomy_info/

whatis.shtml. Accessed December 20, 2012.

Rosalyn Jordan is director of clinical education at RecoverCare, LLC, in

Louisville, Kentucky.

Read More