By Patricia A. Slachta, PhD, RN, ACNS-BC, CWOCN

Assessing moisture and pressure risk in elderly patients continues to be a focus for clinicians in all settings, particularly long-term care. Ongoing research challenges our ideas about and practices for cleansing and protecting damaged skin. Until recently, most wound care clinicians have cleansed long-term care patients’ skin with mild soap and water. But several studies have shown pH-balanced cleansers are more efficient than soap and water for cleansing the skin of incontinent patients.

Various terms are used to describe skin breakdown related to moisture—incontinence-associated dermatitis, perineal dermatitis, diaper rash, intertriginal dermatitis, intertrigo, moisture-related skin damage, moisture-associated skin damage, and even periwound dermatitis. This article uses moisture-associated skin damage (MASD) because it encompasses many causes of skin breakdown related to moisture. Regardless of what we call the condition, we must do everything possible to prevent this painful and costly problem.

Skin assessment

Start with an overall assessment of the patient’s skin. Consider the texture and note dryness, flaking, redness, lesions, macerated areas, excoriation, denudement, and other color changes. (See Identifying pressure and moisture characteristics by clicking the PDF icon above.)

Assessing MASD risk

A patient’s risk of MASD can be assessed in several ways. Two of the most widely used pressure-ulcer risk scales, the Norton and Braden scales, address moisture risk. The Norton and Braden subscales should drive your plan for preventing skin breakdown related to moisture or pressure. The cause of breakdown (moisture, pressure, or shear/friction) must be identified, because treatment varies with the cause.

Both the Norton and Braden scales capture activity, mobility, and moisture scores. The Braden scale addresses sensory perception, whereas the Norton scale identifies mental condition. (See Subscales identifying pressure, shear, and moisture risk by clicking the PDF icon above.) Also, be aware that two scales have been published for perineal risk, but neither has been used widely.

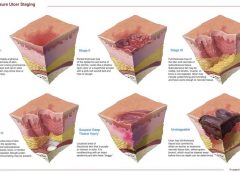

You must differentiate pressure- and moisture-related conditions to determine correct treatment. Patients who are repositioned by caregivers are at risk for friction or shear. Also, know that agencies report pressure-ulcer prevalence. Care providers no longer classify mucous-membrane pressure areas in skin prevalence surveys; mucous membranes aren’t skin and don’t have the same tissue layers. Furthermore, don’t report skin denudement from moisture (unless pressure is present) in prevalence surveys.

When moisture causes skin breakdown

Skin has two major layers—epidermis and dermis. The epidermis itself has five layers: The outermost is the stratum corneum; it contains flattened, keratin protein–containing cells, which aid water absorption. These cells contain water-soluble compounds called natural moisturizing factor (NMF), which are surrounded by a lipid layer to keep NMF within the cell. When skin is exposed to moisture, its temperature decreases, the barrier function weakens, and skin is more susceptible to pressure and friction/shear injury. Also, when urea in urine breaks down into ammonia, an alkaline pH results, which may reactivate proteolytic and lipolytic enzymes in the stool. (See Picturing moisture and pressure effects by clicking the PDF icon above.)

Caring for moisture-related skin breakdown

The standard of care for moisture-related skin breakdown includes four major components: cleanse, moisturize, protect, and contain. Specific products used for each component vary with the facility’s product formulary.

Cleanse

Gently wash the area using a no-rinse cleanser with a pH below 7.0. Don’t rub the skin. Pat dry.

Moisturize

Use creams containing emollients or humectants. Humectants attract water to skin cells and help hold water in the cells; don’t use these products if the skin is overhydrated. Emollients slow water loss from skin and replace intracellular lipids.

Protect

Options for skin protectants include:

• liquid film-forming acrylate sprays or wipes

• ointments with a petroleum, zinc oxide, or dimethicone base

• skin pastes. Don’t remove these products totally at each cleansing, but do remove stool, urine, or drainage from the surface and apply additional paste afterward. Every other day, remove the paste down to the bare skin using a no-rinse cleanser or mineral oil.

Be sure to separate skinfolds and use products that wick moisture rather than trap it. These may include:

• commercial moisture-wicking products

• a light dusting with powder containing refined cornstarch or zinc oxide—not cornstarch from the kitchen or powder with talc as the only active ingredient

• abdominal pads.

Contain

To keep moisture away from skin, use absorbent underpads with wicking properties, condom catheters (for males), fecal incontinence collectors, fecal tubes (which require a healthcare provider order), or adult briefs with wicking or gel properties. Call a certified ostomy or wound care nurse for tips on applying and increasing wear time for fecal incontinence collectors.

If 4″ × 4″ gauze pads or ABD pads are saturated more frequently than every 2 hours, consider applying an ostomy or specially designed wound pouch to the area. Collecting drainage allows measurement and protects skin from the constant wetness of a saturated pad.

Don’t neglect the basics, for example, know that wet skin is more susceptible to breakdown. Turn the patient and change his or her position on schedule. Change linens and underpads when damp, and consider using a low-air-loss mattress or bed or mattress with microclimate technology.

Also, be aware that fungal rashes should be treated with appropriate medications. If the patient’s skin isn’t too moist, consider creams that absorb into the skin; a skin-protecting agent can be used as a barrier over the cream. Besides reviewing and using the standards of care, you may refer to the Incontinence-Associated Dermatitis Intervention Tool, which has categories related to skin damage. See the “Incontinence-Associated Dermatitis Intervention Tool” (IADIT).

Bottom line on skin breakdown

To help prevent skin breakdown related to moisture, assess patients’ skin appropriately, determine treatment using evidence-based guidelines, and implement an appropriate plan of care.

Selected references

Black JM, Gray M, Bliss DZ, et al. MASD part 2: incontinence-associated dermatitis and intertriginous dermatitis: a consensus. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2011;38(4):359-70.

Borchert K, Bliss DZ, Savik K, Radosevich DM. The incontinence-associated dermatitis and its severity instrument: development and validation. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2010;37(5):527-35.

Doughty D. Differential assessment of trunk wounds: pressure ulceration versus incontinence-associated dermatitis versus intertriginous dermatitis. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2012;58(4):20-2.

Doughty D, Junkin J, Kurz P, et al. Incontinence-associated dermatitis: consensus statements, evidence-based guidelines for prevention and treatment, and current challenges. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2012;39(3):303-15.

Gray M, Beeckman D, Bliss DZ, et al. Incontinence-associated dermatitis: a comprehensive review and update. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2012;

39(1):61-74.

Gray M, Black JM, Baharestani MM, et al. Moisture-associated skin damage: overview and pathophysiology. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2011;38(3):233-41.

Langemo D, Hanson D, Hunter S, Thompson P, Oh IE. Incontinence and incontinence-associated dermatitis. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2011;24(3):126-40.

National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel and European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel. Prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers: clinical practice guideline.Washington, DC: National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel; 2009.

Sibbald RG, Krasner DL, Woo KY. Pressure ulcer staging revisited: superficial skin changes & Deep Pressure Ulcer Framework©. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2011;24(12):571-80.

Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society. Guideline for Prevention and Management of Pressure Ulcers. Mt. Laurel, NJ: Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society; 2010.

Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society. Incontinence-Associated Dermatitis: Best Practice for Clinicians. Mt. Laurel, NJ: Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society; 2011.

Zulkowski K. Diagnosing and treating moisture-associated skin damage. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2012;25(5):231-6.

Patricia A. Slachta is an instructor at the Technical College of the Lowcountry in Beaufort, South Carolina.

Read More