Using maggots to treat wounds dates back to 1931 in this country. Until the advent of antibiotics in the 1940s, maggots were used routinely. In the 1980s, interest in them revived due to the increasing emergence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

At Select Specialty Hospital Houston in Texas, we recently decided to try maggot therapy for a patient with a particularly difficult wound. In this case study, we share our experience.

About the patient

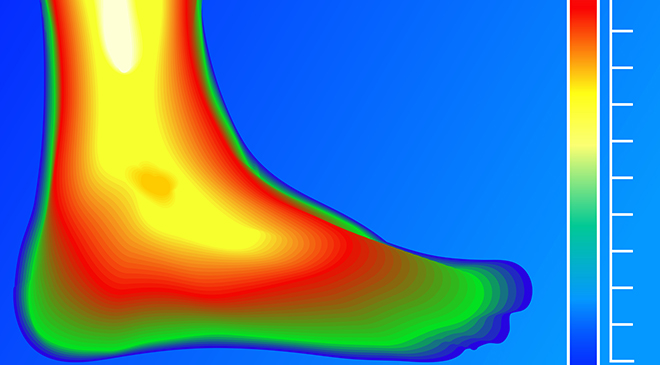

Mr. Green, age 52, had a history of diabetes, which led to bilateral below-the knee amputations. His medical history also included coronary artery disease, peripheral arterial disease, and anemia.

Alert and oriented, he was able to give a detailed account of his recent wound. On August 12, 2015, Mr. Green cut the distal tip of his right third finger while preparing food. Having already lost his legs, he was concerned about the possible need for another amputation, so he made an appointment to see his primary care physician. The physician instructed him to keep his finger clean and dry and to observe it. Nonetheless, it became infected and his finger had to be amputated at the base on September 11. A week later, he was admitted to an acute-care hospital for pain, swelling, and erythema. He received I.V. antibiotics along with pulsed lavage, treatment with Arobella Medical’s Qoustic Wound Therapy System™, ultrasound, and finally, negative-pressure wound therapy (NPWT).

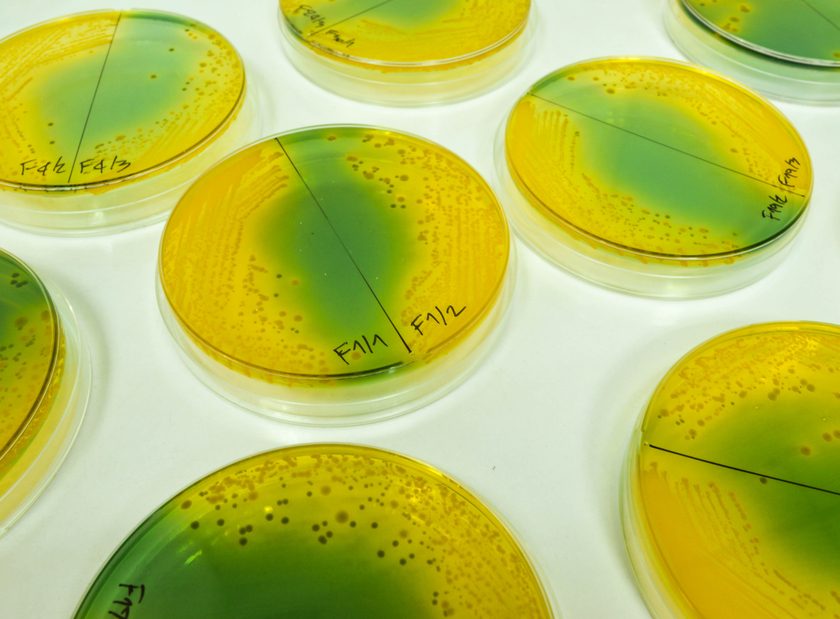

When Mr. Green was admitted to our long-term acute care hospital, the wound bed was pale pink with the hazy, gelatinous look associated with high bioburden tissue, although no bacteriologic testing was done. (See About biofilm.) The wound measured 5 cm x 3.2 cm x 0.9 cm, and lacked the cobblestone appearance usually seen with recently discontinued NPWT.

Maggot therapy

Based on the difficulty of healing this wound, we decided Mr. Green was a good candidate for maggot therapy, which we’d been wanting to introduce into our facility. Mr. Green and his family were concerned about his lack of healing and eager to try maggot therapy. We selected maggots contained within mesh bags because nurses were reluctant to handle free-range ones. (See Maggot application options.)

Applying the maggots

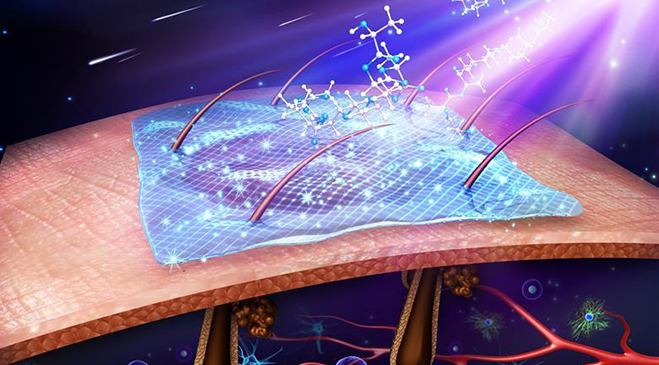

With Mr. Green’s consent, 10 clinical staff members attended the first day of maggot therapy, when the maggot-therapy containment dressing was applied to the wound. Most were surprised to learn that larvae don’t have teeth in their mouths and don’t bite. Instead, they score the wound surface with their mandibles and secrete an enzyme that liquefies the microbes, which they then ingest. The excess fluid is absorbed by the upper dressing.

Applying the containment dressing took 5 minutes. Then zinc oxide cream was rubbed into the periwound skin to protect it from moisture damage and the bag containing the maggots was placed where it contacted the wound bed. Wound location made this a bit difficult, but we managed it by placing multiple pieces of fluffed saline moist gauze on top of the bag and wrapping it firmly with a sterile gauze bandage.

Changes in the wound bed

After 24 hours, the wound bed was predominately a beefy red color and the dressing was saturated. What we’d assumed was slough in the bed actually was a tendon; striae were clearly visible and the surface had a shiny cream color. After 3 days of maggot therapy, the wound bed consisted entirely of moist red granulation tissue. Mr. Green experienced some pain, as would be expected with a wound proximal to nerves in the hand. We also suspected the biofilm had been coating and protecting the nerves until this time, so we chose to remove the maggots with the understanding that the biofilm should have been eradicated.

Additional therapy Mr. Green then underwent NPWT for 1 week, after which antibiotic ointment, petrolatum gauze, and sterile gauze were applied daily until discharge. He was discharged November 25, 2015 with an appointment to see a plastic surgeon to evaluate him for a planned skin graft; at discharge, the wound measured 1.6 cm x 2.5 cm x < 0.1 cm. The plastic surgeon told Mr. Green he’d need no further treatment.

Broadening the treatment options

Engaging other staff members and encouraging them to attend dressing changes contributed to the success of this first use of maggot therapy in our facility. After the first dressing change, Mr. Green’s wound improvement was so dramatic that it made a vivid impact on staff. This motivated them to discuss the results with their coworkers. Soon, staff from other disciplines began to approach me with questions and ask if they could attend the next scheduled dressing change.

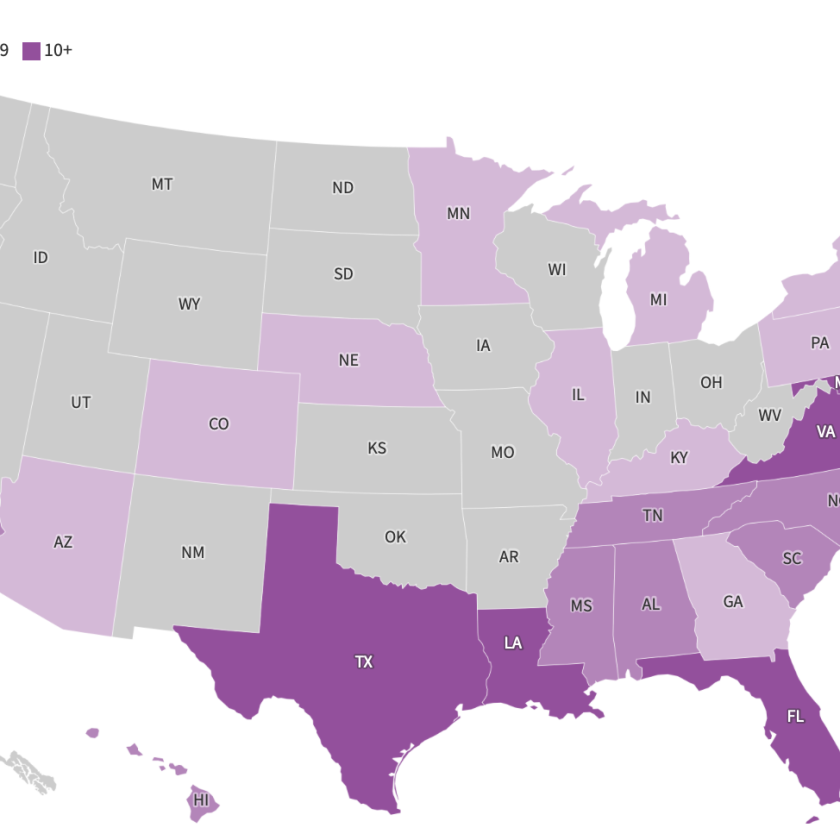

Thanks to the success of our experience, we introduced maggot therapy throughout the Select Specialty Hospitals’ network of facilities in January 2016. Since then, we’ve treated at least a dozen patients.

Sally Anne Jewell is manager of wound care at Select Specialty Hospital Houston in Texas. (Mr. Green’s name in the case study was fictitious.)

Selected references

Cazander G, van Veen KE, Bouwman LH, et al. The influence of maggot excretions on PA01 biofilm formation on different biomaterials. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467(2):536-45.

Cowan LJ, Stechmiller JK, Phillips P, et al. Chronic wounds, biofilms and use of medicinal larvae. Ulcers. 2013.

Geary MJ, Smith A, Russell RC. Maggots down under. Wound Pract Res. 2009;17(1):38.

Steenvoorde P, Jacobi CE, Oskam J. Maggot debridement therapy: free-range or contained? An in-vivo study. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2005;18(8):430-5.