By Christopher O’Donnell, Tampa Bay Times

Debbie King barely gave it a second thought when she scraped her right shin climbing onto her friend’s pontoon for a day of boating in the Gulf of Mexico on Aug. 13.

Even though her friend immediately dressed the slight cut, her shin was red and sore when King awoke the next day. It must be a sunburn, she thought.

But three days later, the red and blistered area had grown. Her doctor took one look and sent King, 72, to the emergency room.

Doctors at HCA Florida Citrus Hospital in Inverness, Florida, rushed King into surgery after recognizing the infection as Vibrio vulnificus, a potentially fatal bacterium that kills healthy tissue around a wound. While King lay on the operating table, the surgeon told her husband she would likely die if they didn’t amputate.

Just four days after the scrape, King lost her leg then spent four days in intensive care.

“The flesh was gone; it was just bone,” she said of her leg.

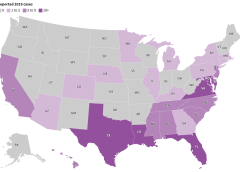

Cases of V. vulnificus are rare. Between 150 and 200 are reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention every year, with about 20% resulting in death. Most are in states along the Gulf of Mexico, but, in 2019, 7% were on the Pacific Coast. Florida averages about 37 cases and 10 deaths a year.

But a rise in cases nationally and the spread of the disease to states farther north — into coastal communities in states such as Connecticut, New York, and North Carolina — have heightened concerns about the bacterium, which can result in amputations or extensive removal of tissue even in those who survive its infections. And warmer coastal waters caused by climate change, combined with a growing population of older adults, may result in infections doubling by 2060, a study in Scientific Reports warned earlier this year.

“Vibrio distributions are driven in large part by temperature,” said Tracy Mincer, an assistant professor at Florida Atlantic University. “The warmer waters are, the more favorable it is for them.”

The eastern United States has seen an eightfold increase in infections over a 30-year period through 2018 as the geographic range of infections shifted north by about 30 miles a year, according to the study, which was cited in a CDC health advisory last month.

The advisory was intended to make doctors more aware of the bacterium when treating infected wounds exposed to coastal waters. Infections can also arise from eating raw or undercooked seafood, particularly oysters, it warned. That can cause symptoms as common as diarrhea and as serious as bloodstream infections and severe blistered skin lesions.

New York and Connecticut this summer issued health warnings about the risk of infection as well. It’s not the first year either state has recorded cases.

“There’s very few cases but when they happen, they’re devastating,” said Paul A. Gulig, a professor in the Department of Molecular Genetics and Microbiology at the University of Florida College of Medicine.

‘An Accident of Nature’

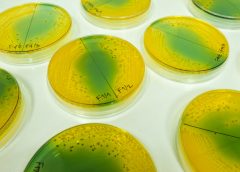

Vibrio has more than 100 strains, including the bacterium that causes cholera, a disease that causes tens of thousands of deaths worldwide each year.

The V. vulnificus strain likes warm brackish waters close to shorelines where the salinity is not as high as in the open sea. Unlike some other Vibrio strains, it has no mechanism to spread between humans.

It’s found in oysters because the mollusks feed by filtering water, meaning the bacterium can become concentrated in oyster flesh. It can enter humans who swim in salty or brackish waters through the slightest cut in the skin. Infections are treated with antibiotics and, if needed, surgery.

“It’s almost an accident of nature,” Gulig said. “They have all these virulence factors that make them really destructive, but we’re not a part of this bug’s life cycle.”

Once inside the human body, the bacteria thrive.

Scientists don’t believe the bacteria eat flesh, despite how they’re often described. Rather, enzymes and toxins secreted by the bacterium as it multiplies break down the human tissue in the area below the skin, causing necrosis, or death of tissue cells.

The infection spreads like wildfire, Gulig said, making early detection critical.

“If you take a pen and mark where the edge of the redness is and then look at that two or four hours later, the redness would have moved,” Gulig said. “You can almost sit there and watch this spread.”

Researchers have conducted studies on the bacteria, but the small number of cases and deaths make it tough to secure funding, said Gulig. He said he switched his research focus to other areas because of the lack of money.

But growing interest in the bacteria has prompted talk about new research at his university’s Emerging Pathogens Institute.

Examining the bacteria’s genome sequence and comparing it with those of Vibrio strains that don’t attack human flesh could yield insights into potential drugs to interfere with that process, Gulig said.

Shock and Loss

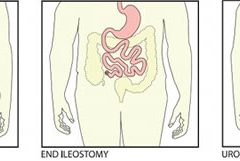

Inside the operating room at HCA Florida Citrus, the only signs of King’s infection were on her shin. The surgeon opened that area and began cutting away a bright red mush of dead flesh.

Hoping to save as much of the leg as possible, the doctor first amputated below her knee.

But the bacteria had spread farther than doctors had hoped. A second amputation, this time 5 inches above the knee, had to be performed.

After surgery, King remained in critical care for four days with sepsis, a reaction to infection that can cause organs to fail.

Her son was there when she awakened. He was the one who told her she had lost her leg, but she was too woozy from medication to take it in.

It wasn’t until she was transferred to a rehab hospital in nearby Brooksville run by Encompass Health that the loss sank in.

A former radiation protection technician, King had always been self-reliant. The idea of needing a wheelchair, of being dependent on others — it felt like she had lost part of her identity.

One morning, she could just not stop crying. “It hit me like a ton of bricks,” she said.

Six different rehab staffers told her she needed to meet with the hospital’s consulting psychologist. She thought she didn’t need help, but she eventually gave in and met with Gerald Todoroff.

In four sessions with King, he said, he worked to redirect her perception of what happened. Amputation is not who you are but what you will learn to deal with, he told her. Your life can be as full as you wish.

“They were magic words that made me feel like a new person,” King said. “They went through me like music.”

Physical therapy moved her forward, too. She learned how to stand longer on her remaining leg, to use her wheelchair, and to maneuver in and out of a car.

Now, back in her Gulf Coast community of Homosassa, those skills have become routine. Her husband, Jim, a former oil company worker and carpenter, built an access ramp out of concrete and pressure-treated wood for their single-story home.

But she is determined to walk with the aid of a prosthetic leg. It’s the motivation for a one-hour regimen of physical therapy she does on her own every day in addition to twice-weekly sessions with a physical therapist.

Recovery still feels like a journey but one marked by progress. She has nicknamed her “stump” Peg. She’s now comfortable sharing before and after pictures of her leg.

And she’s made it her mission to talk about what happened so more people will learn about the danger.

“This is the most horrific thing that can happen to anybody,” she said. “But I’d sit back and think, ‘God put you here for a reason — you’ve got more things to do.’”

What to Know About ‘Flesh-Eating’ Bacterium Vibrio vulnificus

Infection Symptoms:

- Diarrhea, often accompanied by stomach cramping, nausea, vomiting, and fever.

- Wound infections cause redness, pain, swelling, warmth, discoloration, and discharge. They may spread to the rest of the body and cause fever.

- Bloodstream infections cause fever, chills, dangerously low blood pressure, and blistering skin lesions.

To Protect Against Vibrio Infections:

- Stay out of saltwater or brackish water if you have a wound or a recent surgery, piercing, or tattoo.

- Cover wounds with a waterproof bandage if they could come into contact with seawater or raw or undercooked seafood and its juices.

- Wash wounds and cuts thoroughly with soap and water after contact with saltwater, brackish water, raw seafood, or its juices.

Who Is Most at Risk:

- Anyone can get a wound infection. People with liver disease, cancer, or diabetes, and those over 40 or with weakened immune systems, are more likely to get an infection and have severe complications.

Sources:

This article was produced in partnership with the Tampa Bay Times.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

Read More

Martha Kelso, RN, HBOT, CEO, WCP Wound Care Plus, LLC, is the founder and Chief Executive Officer of Wound Care Plus, LLC (WCP). As a visionary and entrepreneur in the field of mobile medicine, she has operated mobile wound care practices nationwide for many years. She enjoys educating on the art and science of wound healing and how practical solutions apply to healthcare professionals today. Martha enjoys being a positive change in healthcare impacting clients suffering from wounds and skin issues of all etiologies. Martha started her career as a Certified Nurse Aide at the age of 15 in Kansas before moving to Kansas City, MO to attend nursing school. Long Term Care nursing was her first love and her biggest challenge.

Martha Kelso, RN, HBOT, CEO, WCP Wound Care Plus, LLC, is the founder and Chief Executive Officer of Wound Care Plus, LLC (WCP). As a visionary and entrepreneur in the field of mobile medicine, she has operated mobile wound care practices nationwide for many years. She enjoys educating on the art and science of wound healing and how practical solutions apply to healthcare professionals today. Martha enjoys being a positive change in healthcare impacting clients suffering from wounds and skin issues of all etiologies. Martha started her career as a Certified Nurse Aide at the age of 15 in Kansas before moving to Kansas City, MO to attend nursing school. Long Term Care nursing was her first love and her biggest challenge.