The FDA-approved skin substitute reduces inflammation and transforms chronic wounds into acute injuries.

Six hours north of Reykjavik, along a narrow road tracing windswept fjords, is the Icelandic town of Isafjordur, home of 3,000 people and the midnight sun. On a blustery May afternoon, snow still fills the couloirs that loom over the docks, where the Pall Palsson, a 583-ton trawler, has just returned from a three-day trip. Below the rust-spotted deck, neat boxes are packed with freshly caught fish and ice. “If you take all the skins from that trawler,” says Fertram Sigurjonsson, the chairman and chief executive officer of Kerecis Ltd., gesturing over the catch, “we would be able to treat one in five wounds in the world.”

Iceland has a long history of working with fish leather. “My grandfather’s first shoes were the skin of a catfish,” Sigurjonsson says. Instead of kilometers, Icelanders used to mark distance in worn-out fish shoes. Sigurjonsson and his small company have spent the past nine years applying this tradition to the treatment of chronic wounds, those that take longer than a month to heal.

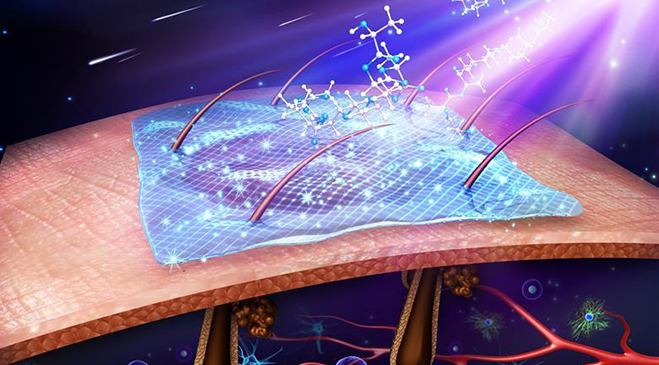

The materials in fish skin, particularly omega-3 fatty acids, yield natural anti-inflammatory effects that speed healing. When placed on wounds, the product, made from dried and processed fish skin, works as an extracellular matrix, a group of proteins and starches that plays a crucial role in recovery. In a healthy person, a matrix surrounds cells and binds them to tissue, generating the growth of new epidermis. But in chronic wounds, this natural structure fails to form. So like a garden trellis, the fish skin provides the body’s own cells a structure to grow around so they can form healthy tissue, gradually becoming incorporated into the closing wound.

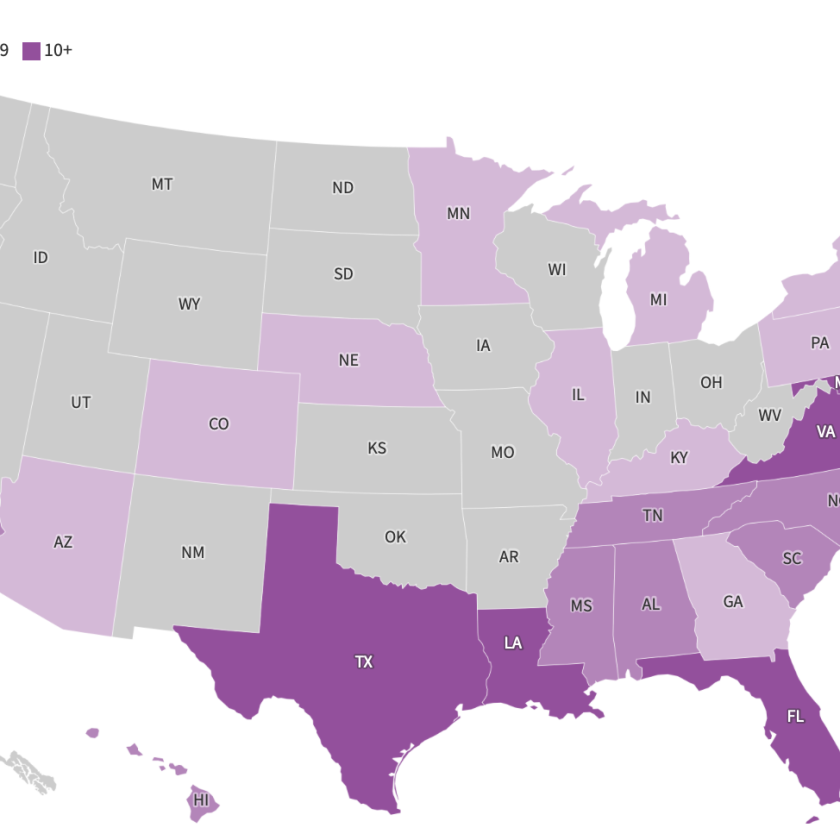

Some six and a half million Americans suffer from chronic wounds, whether related to vascular disease, diabetes, or complications from normal procedures. The five-year survival rate is 54 percent, compared with 88 percent for breast cancer, and treatments cost more than $25 billion a year. That total is steadily rising, in part because of a graying population. But precisely because many patients suffering from such wounds tend to be old, and many are also poor, they don’t get much attention.

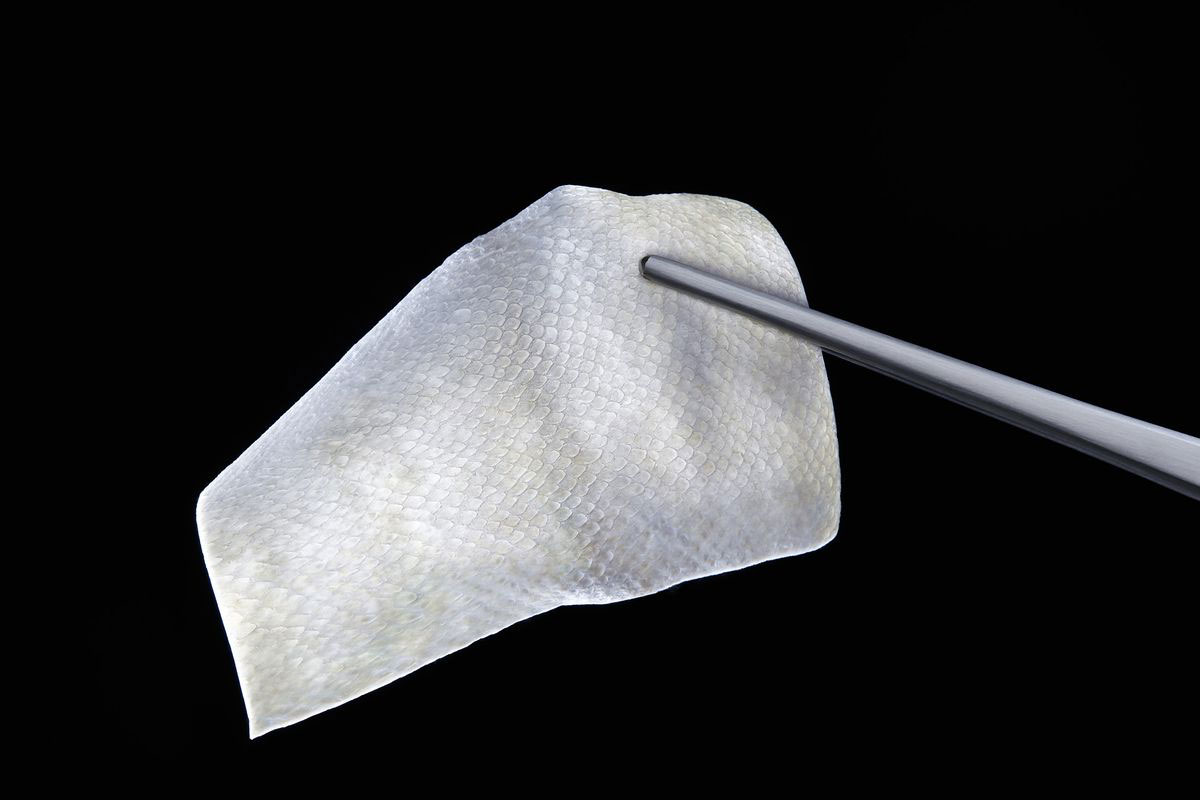

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration approvedKerecis’s fish skin treatment, Omega3 Wound, late last year. The market for skin substitutes isn’t for the squeamish. Rival products include material from pig intestines, fetal cows, the innermost layer of human amniotic tissue, and cadavers. (There are also synthetics made of silicone and other materials.) It can be tough to compare medical outcomes, as clinical trials are small and disease-specific. But generally, because of the viral disease transfer risk, human- and animal-derived products require heavy processing and tend not to work well in infected wounds. That’s one of Kerecis’s talking points, as the only FDA-approved skin substitute derived from fish: Because of our evolutionary differences, there’s less disease risk and therefore less processing required. When Sigurjonsson makes this case on the trawler, leaning over his latest catch, he’s fairly persuasive.

“My first memories are of fish,” the CEO says, poking at a machine he designed to help dry out the skin. Like many men here, Sigurjonsson spent his boyhood summers working in processing plants, cleaning the catch or driving forklifts. After earning a graduate degree in innovation and product management from the Technical University of Denmark, he started working at prosthetics maker Ossur, where he saw many amputees develop chronic wounds around their replacement limbs. An impromptu move to New Zealand got him thinking about substituting natural materials while running business development for Keratech, a company that dressed wounds with sheep wool. When he returned to Iceland, he started wondering what fish skin could do for a wound dressing.

Today, from the Isafjordur docks, trucks haul the fish to a commercial processing facility down the road. There the fish land on a conveyor belt, where in short order they get filleted and skinned. The meat is sold as food. Twice a week, a Kerecis employee comes early in the morning with a few Styrofoam boxes to collect skins of the right size, age, and species—the company uses plentiful, fatty cod.

The medical manufacturing takes place on the third floor of an old fish processing plant a few blocks away, beside a graveyard where Sigurjonsson’s forefathers rest and a larger-than-life statue depicts two men in slickers hauling a net. The facility has a sweeping view of the fjord; on a recent tour with potential clients, a pod of whales made a cameo. Inside, the fish skin is gently agitated in a water bath for a few days. “You need to get the mucus away, but we didn’t want to use harsh chemicals or wash away the fats or elastin,” Sigurjonsson says, referring to the protein that makes skin flexible. Then the skin enters a decontaminated room, where it’s placed in a dehydrator for about two days. Once dry, it’s cut into squares and sterilized. At that point, Sigurjonsson says, “one gram of fish skin is worth more than a gram of gold.”

Baldur Tumi Baldursson, Kerecis’s medical director, holds the jiggering wheel of his heavily customized Toyota Land Cruiser as it careens up the Langjokull Glacier, Iceland’s second-largest ice cap. While his carefully deflated 38-inch tires struggle to find purchase, the physician recalls how the early team often had to improvise. At one point, to identify mice in an animal trial, he found himself searching YouTube for how-to videos on tattooing.

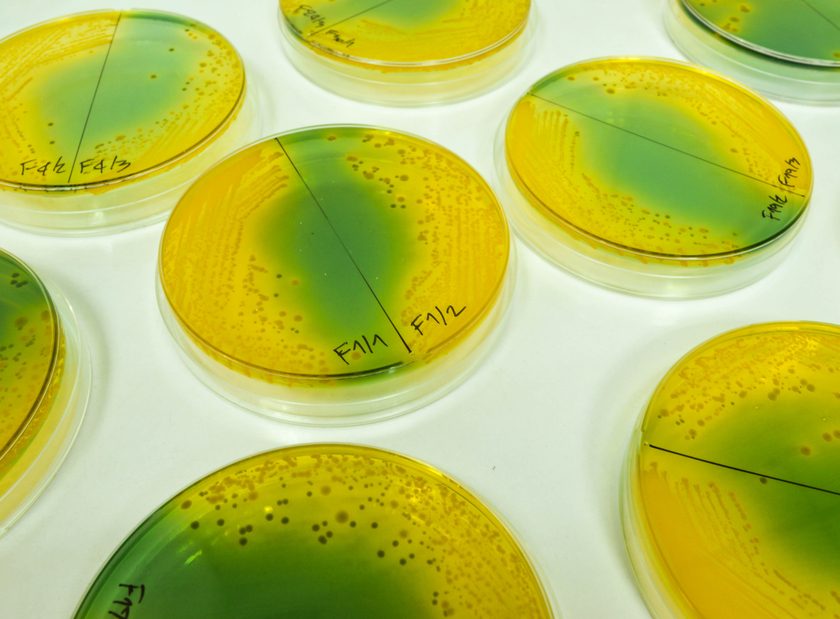

Baldursson was the lead author on Kerecis’s most extensive clinical trial in 2015. Testing on 162 people showed that Kerecis healed acute wounds faster than the leading product, a pig intestine compound called Oasis Wound Matrix. “It has the potential to be very useful,” says Steven Jeffery, a plastic surgeon with the U.K. military who specializes in burn care. (He does, however, warn patients about the fishy smell.)

Jeffery isn’t the only burn surgeon interested in Kerecis’s tissue growth capabilities. The U.S. Department of Defense is on the lookout for better burn treatments because of the increase in service wounds from improvised explosive devices. In a study conducted with the U.S. Army Institute of Surgical Research, the fish skin bested the healing rates of cadaver skin, a common military treatment for burns. The Army has also funded several further studies, showing that unlike rival products, fish skin can ward off bacteria in infected wounds and reduce bleeding. “Both are very important things for acute blast injuries,” says Kerecis’s clinical R&D director, Hilmar Kjartansson, because the extreme wounds that result are often contaminated by flying debris.

Kerecis now owns one of the largest buildings in Isafjordur, and is a rare source of skilled employment in the remote town, where most flights get canceled and the main road was only paved 10 years ago. In the first three months of 2017, the company says, it sold as much Omega3 Wound as it did the previous year, though it wouldn’t provide any hard numbers or say whether it’s profitable. It’s adding staff and gradually upgrading its homemade equipment.

At Mount Sinai Saint Luke’s Hospital in New York, John Lantis, the chief of vascular and endovascular surgery and a Kerecis adviser, says its treatment has become a valuable weapon against the “shadow epidemic” of chronic wounds. On a recent afternoon, he’s an hour late finishing his rounds. One of his final patients is an old woman with a mat of gray curls and a sweet, cloudy gaze. With her pants rolled up, you can see skin hanging in strips off her shin.

Lantis props her foot in his lap to clean up the area, and she closes her eyes as he pulls out a thin, whitish square of fish skin to cover the sore. Up close, the pockets that used to hold scales form a herringbone pattern, the only sign of its origin. He covers the open wound, tapes the fish skin in place, and binds it into a neat compression dressing. The whole procedure takes 10 minutes. “Wound care is like the Wal-Mart of medicine,” he says afterward. “Everyone shops there, but no one talks about it.”

Even with FDA approval and successful firsthand experience, it’s been hard to get Omega3 Wound added to hospital treatment lists in the U.S. The problem, Lantis says, is that costs increasingly dictate prescribed treatments, so even products that raise patient recovery rates can struggle to break into the market. Often, he says, “you know what’s best for your patient, but you’re going to lose money taking care of them.” This is where age and class tend to play a role.

In Iceland, Sigurjonsson says, “Because the population is so small, if you’re going to be successful, you need to appeal to many people. You can never lose sight of the bigger picture.”

Kerecis’s next step, slated for fall, is a human clinical trial for burn care to be conducted with Army researchers and Jeffery, the British surgeon. The company is also expanding into other product lines. In Iceland, it’s selling an over-the-counter skin-care line with high concentrations of omega-3 fatty acids. It has received FDA approval for a staple reinforcement to be used during internal surgeries, and just completed a clinical study in Mexico for an oral surgery product, meant for gum recession or oral grafting. The company is also experimenting with a reconstructive membrane that could help heal hernias, speed breast reconstruction, or support the dura, the thick membrane between the brain and spinal cord.

In each of these applications, one of the most promising results of the fish skin is its ability to reduce inflammation, a major obstacle to the healing process, and transform chronic wounds into mere acute injuries, such as burns. “I tell my students, your work is inflammation,” says Baldursson. “Practically all of internal medicine is just fighting inflammation.”

Although the hows and whys aren’t yet understood, reducing inflammation may also lead to pain reduction. Bjarni Hákonarson, a middle-aged IT specialist, was diagnosed with oral cancer in 2012 and has since undergone two rounds of radiation, chemotherapy, and extensive surgery, including several muscle grafts and the removal of part of his jawbone. He showed up at Baldursson’s clinic earlier this year after hearing about Kerecis in the local news. At the time, Hákonarson’s mouth was so swollen from his wound (and operations) that the doctor couldn’t see the injury site. But with a graft of fish skin, he says, “to my astonishment, all pain disappeared.” The swelling ebbed, too.

Sitting in a coffee shop in Reykjavik, Hákonarson has a scarf tucked up under his chin to hide that half of it is missing. “As you can see, I know pain pretty well,” he says. The mouth sore that caused the agony is probably cancer and therefore not worth trying to heal. Still, “to see the clarity coming back to your thoughts, that’s beautiful,” he says. “If you can see your future relatively free of pain, that’s a lot of quality to look forward to.”