By Tamera L. Brown, MS, RN, ACNS-BC, CWON, and Jessica Kitterman, BSN, RN, CWOCN

Pressure ulcers take a hefty toll in both human and economic terms. They can lengthen patient stays, cause pain and suffering, and increase care costs. The average estimated cost of treating a pressure ulcer is $50,000; this amount may include specialty beds, wound care supplies, nutritional support, and increased staff time to care for wounds. What’s more, national patient safety organizations and insurance payers have deemed pressure ulcers avoidable medical errors and no longer reimburse the cost of caring for pressure ulcers that develop during hospitalization.

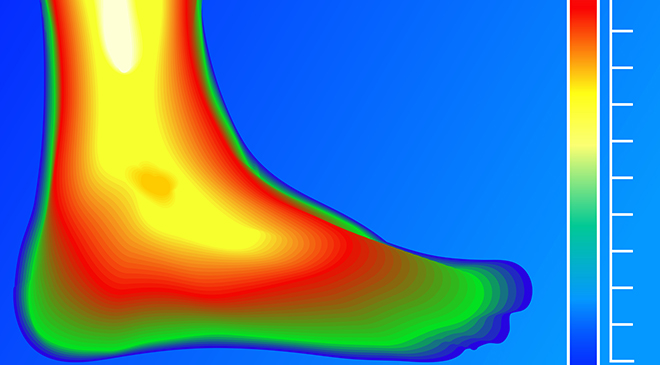

The National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel defines a pressure ulcer as a localized injury to the skin, underlying tissue, or both, which usually arises over a bony prominence as a result of pressure or pressure combined with shear. Research suggests various contributing factors, including smoking, obesity, reduced sensation, and advanced age. The unique contribution of each factor remains unclear.

The authors of this article are wound ostomy continence (WOC) nurses at Indiana University Health Ball Memorial Hospital, a 350-bed teaching hospital in Muncie, Indiana. We track and document pressure-ulcer statistics on a monthly basis. When pressure-ulcer rates approach or exceed national benchmarks, we’re responsible for investigating the root causes of the increase and designing and deploying strategies to strengthen preventive practices. In this article, we share our most recent approach.

An unexpected call to action

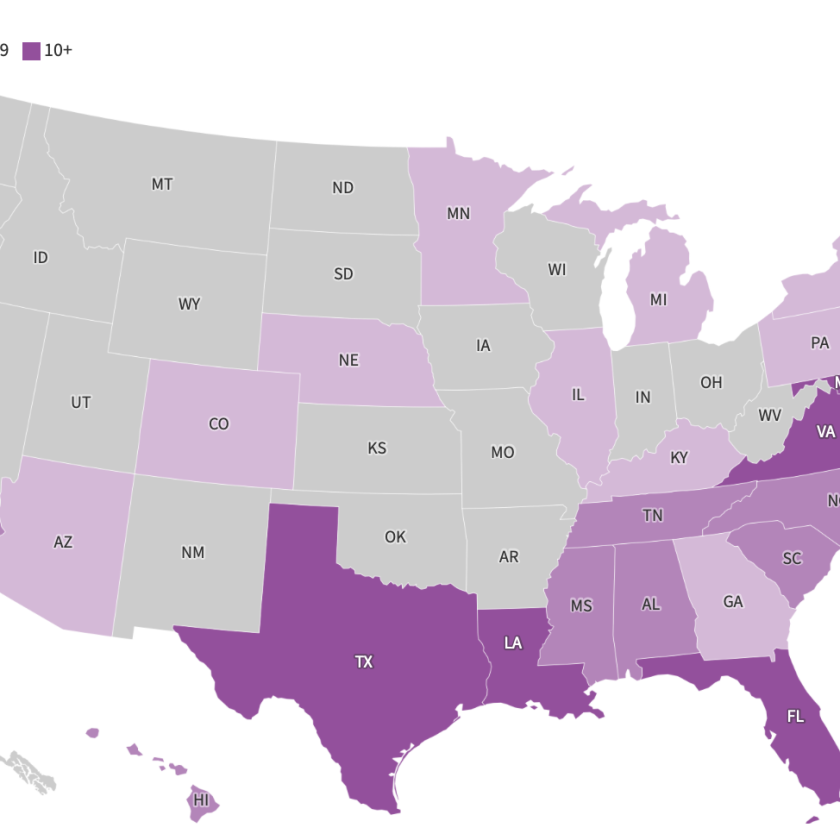

In March 2011, our hospital-wide monthly pressure-ulcer count jumped from its usual range of four to six cases to 26 cases—well above averages from the National Database of Nursing Quality Indicators® for our comparative hospital group. Uncertain what caused this sudden increase, we nonetheless knew we had to take dramatic and rapid action. After all, the ulcer count had increased suddenly despite the education we’d provided clinicians about skin-care products, interventions, and yearly skin and wound fairs.

We researched possible associated factors and all available preventive programs, starting with the hospital’s current skin-product vendors. We’d been using effective products and underpads—but had we thoroughly educated all involved staff on other preventive strategies? We then brainstormed new options with a broad group of stakeholders, including our chief nursing officer. We included unit-based skin-care champions in discussions to gain their perspectives. We also identified major factors to address:

• Optimal use of exceptional products

• Education for all nursing personnel

• How to integrate evidence-based strategies into practice.

We found our hospital qualified for educational support from a vendor because we were already using two of its products (the skin-care line and underpads). The vendor would supply us with educational materials, guide the rollout of a more comprehensive prevention program, and evaluate our anticipated cost savings. Once we made this decision, we met with the vendor, managers, and educators to devise a schedule for each unit and a time frame to complete education on the new program.

New pressure-ulcer prevention program

Goals of our pressure-ulcer prevention (PUP) program were to reduce pressure ulcers through nurse education, product optimization, integration of best practices for all nurses, and measurement of clinical and economic outcomes. The key was to reach all nurses and nurse technicians. The previously adopted skin-care line (which we kept) included wicking underpads and five skin products with specific guidelines for use with certain populations.

Unit-based skin-care champions conducted trials of the PUP program, with oversight by WOC nurses. Our facility has approximately 22 skin-care resource nurses—one or two from each unit that tested the program. This pilot test yielded information to determine feasibility and cost effectiveness. With the time, resources, and expenses required, would this program work for us? We decided the answer was yes.

Implementing the program

House-wide implementation began with educational sessions for registered nurses (RNs) and certified nurse technicians (CNTs). Each care provider studied an educational workbook designed for his or her professional role, and completed a pretest and posttest. Scores ranged from low to medium on the pretest and from upper medium to high on the posttest. Staff received 4 hours of paid time for the pretest, workbook completion, and posttest. Nursing personnel singled out the easy-to-read format and detailed illustrations as the book’s particular strengths. (See Key teaching points for nurses by clicking the PDF icon above.)

Providing role-specific education for unlicensed personnel was a new approach for us—one we believed would prove crucial to our eventual success. We started the new program and education on two to three units at a time, beginning with the units that had the highest pressure-ulcer rates. We met with managers and educators, formulated a unit-specific plan, and implemented the PUP. To follow up, WOC nurses visited every nursing unit and held small-group and one-on-one conversations with staff. One unit required all CNTs to spend 4 hours with us to receive more one-on-one education. CNTs reported that these sessions empowered them and showed them that the hospital valued their role in patient care.

We required each staff member to demonstrate proper use of skin-care products (nourishing cream and protective cream), strategies to prevent heel ulcers (protective boots or pillows positioned lengthwise), proper turning techniques (use of two pillows rather than one, along with 30-degree turns), and use of appropriate barrier creams (zinc oxide vs. dimethicone) and wicking underpads. During our time on the units, we developed relationships with direct-care nurses and CNTs and made ourselves accessible for questions or concerns.

Unit-based skin-care champions were instrumental in informing, inspiring, auditing, and coaching their peers in integrating these new practices. Each unit’s data were shared frequently with stakeholders at all organizational levels, and unit leaders were held accountable for action plans.

Tracking the results

After the PUP was implemented, we tracked pressure-ulcer rates diligently for 12 months. About midway through the program, five units went 5 months without pressure ulcers. We suspected a competition might be going on; the staff on those units seemed to be racing to see which unit could go the longest without a pressure ulcer. Every few months, we put reminders in the nursing newsletter and had managers remind staff about turning, keeping patients’ heels off the bed, and using barrier creams and wicking underpads.

When we learned of a particularly bad pressure ulcer, we performed a root cause analysis (RCA) to determine the cause, and discussed stage I and II ulcers one-on-one with the involved staff members to find the cause. The RCA became an invaluable tool for focusing on contributing factors. Nursing report cards with pressure-ulcer rates were reported monthly to all units. Ultimately, we discovered that failure to use a proper barrier cream and assess beneath mechanical devices (such as tubing) was a major contribution to pressure ulcers.

We celebrated with the units that reduced their ulcer rates the most or made it to zero ulcers, with unit managers and WOC nurses providing pizza and other treats. Recognition by our chief nursing officer and chief executive officer was a welcome surprise.

Evidence-based outcomes

Over the next 12 months, hospital-wide nosocomial pressure ulcers fell by up to 23 ulcers per month. Ten of 10 units consistently outperformed national benchmarks quarterly. Particularly notable (with use of the new product line) was an immediate decrease in incontinence-associated dermatitis, which contributes to pressure ulcers.

By April 2012, our facility had accumulated savings of $2,720,340 and our monthly hospital-wide pressure ulcer count was down to four. The PUP program proved to be so effective that all new RNs and CNT hirees now are required to complete the program and shadow WOC nurses for 4 hours of education. (See Evidence-based outcomes by clicking the PDF icon above.)

By using strategic PUP products along with education and interactive training tools, our facility significantly reduced hospital-acquired pressure ulcers, increased the knowledge base of our professional staff and nurse technicians, and saw significant cost savings. We’re still using the PUP program today to help keep our pressure-ulcer rate low.

Selected references

Armstrong DG, Ayello EA, Capitulo KL, et al. New opportunities to improve pressure ulcer prevention and treatment: implications of the CMS inpatient hospital care present on admission indicators/hospital-acquired conditions policy: a consensus paper from the International Expert Wound Care Advisory Panel. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2008;21(10):469-78. doi:10.1097/01.ASW.0000323562.52261.40

National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel, European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel. Pressure ulcer prevention recommendations. In: Prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers: clinical practice guideline. Washington, DC: National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel; 2009:21-50.

The authors work at Indiana University Health Ball Memorial Hospital in Muncie. Tamera L. Brown is a wound ostomy clinical nurse specialist. Jessica Kitterman is a wound ostomy nurse.

Patient has stage 2 pressure ulcer – treating with turning and betadine and no barrier cream. Turning should it be every two hours and is the positioning only side to side? What about the bed surface? Is the air bed good?

Low air loss bed good, Waffle mattress effective as well. Turning every two should be for ALL patients. Not certain why the betadine for the pressure ulcer? We rarely use betadine anymore. Toxic to good/new tissue. We use a hydrocolloid dressing or foam dressing (ie. Mepilex) for stage II pressure ulcers. Hope this helps.