By Gail Hebert, RN, MS, CWCN, WCC, DWC, LNHA, OMS; and Rosalyn Jordan, BSN, RN, MSc, CWOCN, WCC, OMS

Imagine your physician has just told you that your rectal pain and bleeding are caused by invasive colon cancer and you need prompt surgery. She then informs you that surgery will reroute your feces to an opening on your abdominal wall. You will be taught how to manage your new stoma by using specially made ostomy pouches, but will be able to lead a normal life.

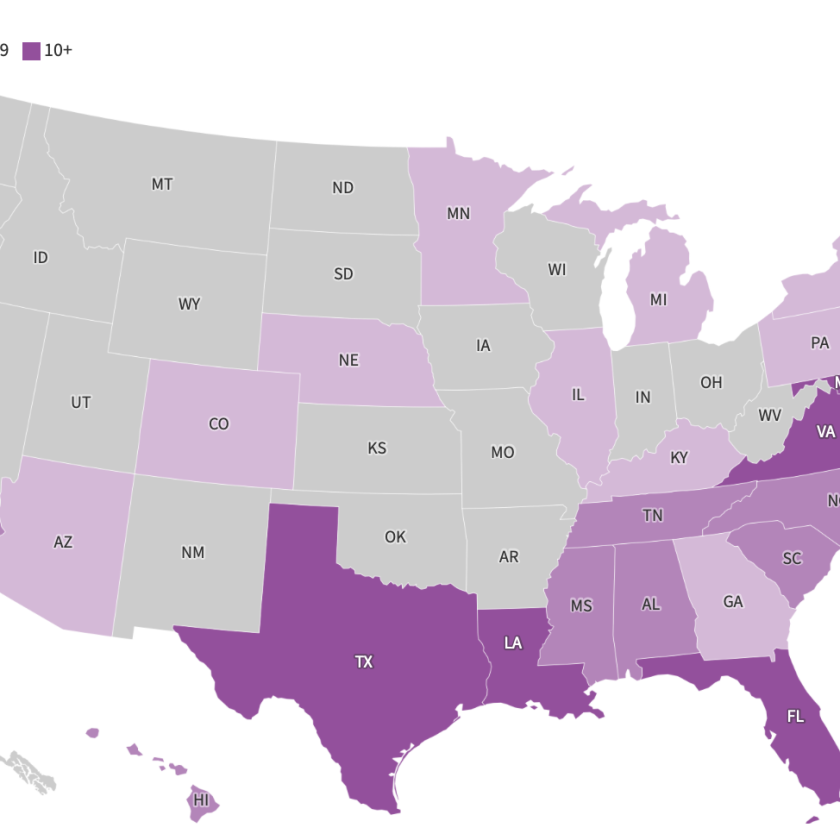

Like most people, you’d probably be in shock after hearing this. More than 700,000 people in the United States are living with ostomies. Every year, at least 100,000 ostomy surgeries are done, preceded by a conversation much like the one above. So how do patients recover from the shock of learning about their pending surgery—and then return to a full life?

Although each patient goes through the process differently, interviews and studies of patients reveal several common reactions—concerns about a negative body image, anxiety over whether they’ll be able to care for the stoma, and worries over how the stoma will affect their relationships. (See Ostomy shock: How patients react by clicking the PDF icon above.)

Psychological adaptation

According to the United Ostomy Associations of America (UOAA), patients who’ve had ostomy surgery tend to follow a similar path of adjusting their life skills, based on the consequences of their specific surgery. Typically, they go through the four recovery phases below. However, these phases aren’t as cut and dried as they might seem. Patients adjust at their own individual rates. Some may experience the phases in a different order, may skip a phase, or may regress and pass through one or more phases multiple times.

• Shock or panic. This phase occurs immediately after learning of the need for an ostomy, or right after surgery in some cases. Patients seem distracted and anxious, unable to focus on or participate in teaching and demonstration sessions. They have trouble retaining information (including patient teaching) during this phase, which commonly lasts days to weeks.

• Defense, retreat, or denial. The patient practices avoidance techniques, may refuse to participate in stoma care, and may exhibit defensive behaviors. This phase may last weeks to months.

• Acknowledgement. During this phase, the patient starts to accept the reality of living with a stoma. As this phase begins, some patients may exhibit lack of interest, sadness, hopelessness, and anxiety. Some are angry and blame others for their condition.

• Adaptation and resolution. Anger and grief decrease and patients learn to cope with their circumstances constructively. This phase may take up to 2 years to achieve.

Whichever recovery phase they’re in, ostomy patients can gain solace by knowing others in their situation are going through the same recovery process. Direct them to www.ostomy.org/supportgroups.shtml for help finding a support group (if desired). Tell them about helpful videos; for example, “Living with an Ostomy” from UOAA features patients talking about their experience.

Some patients may wish to express their feelings through painting, drawing, writing, or other art forms. For some, a referral to a psychologist or therapist may be warranted.

How clinicians can help

Studies show a patient’s return to full functioning after ostomy surgery depends on the quality and consistency of patient teaching. The need for effective patient education makes us acutely aware that teaching isn’t simply about reciting facts. To provide effective teaching, first determine where your patient is in the recovery process by gauging his or her emotional needs. For instance, a patient who’s angry and in denial isn’t ready to learn the details of stoma management. During the adaptation and resolution process, clinicians must maintain a supportive and understanding approach to help the patient accept body changes and regain the previous quality of life. Maintaining a compassionate approach makes this easier.

Compassion counts

The role of the ostomy specialist is to provide patient teaching, coupled with good clinical skills and compassion. For some patients, your ability to convey compassion may be more important than any other aspect of the care you provide. The following story illustrates this point.

A home health patient had been married for 49 years and was looking forward to his 50th wedding anniversary. But then he was hospitalized for a bowel obstruction due to colon cancer, and had to have an ileostomy. His diagnosis was terminal. His wife chose to care for him at home with the help of a local hospice organization. Within a few days, both were at wit’s end because of his continuous severe pain. Also, they couldn’t maintain the seal on the pouching system, and effluent leakage had severely denuded his entire abdomen. The regular hospice nurse was empathetic, but couldn’t maintain the pouch seal for more than 2 or 3 hours. The nurse’s agency contacted an ostomy management nurse specialist, who used her clinical expertise to relieve the pouching problem and resolve the pain.

The ostomy nurse used her compassion to resolve the next issue: The patient had two things on his “bucket list.” He wanted to travel to his son’s home to visit one last time, and he wanted to be present for his 50th anniversary celebration. His wife hired a driver for the road trip, and the ostomy nurse helped by mapping out the trip route and making arrangements for trained ostomy nurses along the way to be available in case their services were needed. She packed individual pouching supplies and included detailed pouch-change instructions in writing.

The patient and his wife had a successful road trip with the help of nurses along their route. They returned home to a beautiful anniversary celebration. Both were happy. He was at home with his wife—the love of his life for 50 years. Several days later, he died in his sleep. His wife expressed thanks for the expertise that had helped relieve her husband’s pain in his last days. But she said the “above and beyond” actions the ostomy nurse had taken in arranging for their road trip had made the biggest difference to them as they approached their final goodbyes.

Long-term care needs

Ostomy patients continue to need professional care for many years. Patients are concerned about food, clothing, and ostomy appliances, which can lead to a consistent need for specially trained clinicians to help them cope with the challenge of living with an ostomy. Even when patients reach the adaptation phase and have accepted this challenge, difficulties may occur. At any point, they may need to adjust and adapt to a specific concern. When they do, trained ostomy professionals must be available to provide skilled evaluation and education. In fact, patients with ostomies (and their family members) require care throughout the life span.

Patients with stomas may need assistance, counseling, training, and care at any time—to help them cope with a new or recurring problem or to maintain an optimistic view and learn how to make needed adjustments. The Ostomate Bill of Rights from UOAA states: “The ostomate shall have post-hospital follow-up and life-long supervision.” If you’re among those who care for ostomates, make sure that life-long supervision includes a generous portion of compassion.

Selected references

Aronovitch SA, Sharp R, Harduar-Morano L. Quality of life for patients living with ostomies: influence of contact with an ostomy nurse. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2010:37(6):649- 53.

Nichols TR, Riemer M. The impact of stabilizing forces on postsurgical recovery in ostomy patients. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2008:35(3):316-20.

Prinz A. Healing from Ostomy Surgery. Colostomy New Patient Guide. 2011. The Phoenix. www.ostomy.org/ostomy_info/pubs/UOAA_NPG_Colostomy_2012.pdf. Accessed July 15, 2013.

Sun V, Grant M, McMullen CK, et al. Surviving colorectal cancer: long-term, persistent ostomy-specific concerns and adaptations. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2013;40(1):61- 2.

United Ostomy Associations of America, Inc. What is an Ostomy? www.ostomy.org/ostomy_info/ whatis.shtml. Accessed July 2, 2013.

Gail Hebert is a clinical Instructor with the Wound Care Education Institute in Plainfield, Illinois. Rosalyn Jordan is senior director of Clinical Services at RecoverCare, LLC, in Louisville, Kentucky.

Dear Gail and Rosalyn,

Two years ago I received the news that I needed to have a total proctocolorectomy due to suffering from many years of Ulcerative Colitis. I remember thinking the hardest thing about this surgery was learning how to keep my pouches on so that I could go back to my fulltime job as a Registered Nurse. I did have a home-care nurse come to the house but she was not very empathetic or did she show any compassion, that’s when I decided that I’m going to take your OMS course and help other ostomates like myself! I recently passed the certification and am excited about my future; I want to help others that have had to face what I did and, be there for them! I have learned and gained much information from your course and also from living this lifestyle.

I do believe that I am going to take your Wound Care course, also. Thank you for making it possible to become certified in these speciality fields!

Sincerely Yours,

Sandra McAfee

Congratulations Sandra on your OMS certification. Your positive attitude and spirit are so inspiring! The NAWCO and persons with an ostomy are so lucky to have someone like you!

I am a ostomy specialist in South Korea , and I have learned a lot from the story above.

I have recently treated ostomates without a compassionate approach but , now i feel ashame of myself and have realized how a big difference we can make by empathetic concerns and compassions. Thanks a lot!

Hi-

Just stumbled upon your website. I had my ileostomy at 21 following 6 years of misdiagnosis, pain and a potentially fatal abcess.

At that point, they could have cut off my limbs- I just wanted to be “well” and get back to college and living. ( although when I began to feel better I did throw an ostomate volunteer out of my room in a fit of denial and rejection.)

Today, 40+ years later I’m married with 2 children, a university professor with a doctorate, a private practice in grief counseling, a scuba diver, acid swimmer and sailor.

I travelled alone to South Africa on a Fulbright and avocationally have travelled the world.

I am not bragging, just proud of my accomplishments. I also do motivational speaking on living a positive, meaningful life.

Thanks for listening!

Mari