Carol Emanuele beat cancer. But for the last two years, the Philadelphia woman has been fighting her toughest battle yet. She has an open wound on the bottom of her foot that leaves her unable to walk and prone to deadly infection.

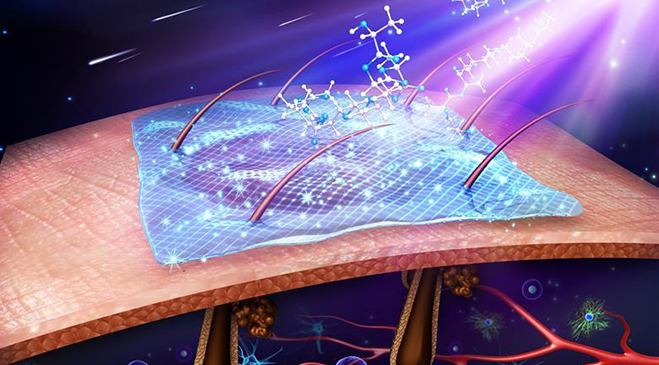

In an effort to treat her diabetic wound, doctors at a clinic in Northeast Philadelphia have prescribed a dizzying array of treatments. Freeze-dried placenta. Penis foreskin cells. High doses of pressurized oxygen. And those are just a few of the treatment options patients face.

“I do everything, but nothing seems to work,” said Emanuele, 59, who survived stage 4 melanoma in her 30s. “I beat cancer, but this is worse.”

The doctors who care for the 6.5 million patients with chronic wounds know the depths of their struggles. Their open, festering wounds don’t heal for months and sometimes years, leaving bare bones and tendons that evoke disgust even among their closest relatives.

Many patients end up immobilized, unable to work and dependent on Medicare and Medicaid. In their quest to heal, they turn to expensive and sometimes painful procedures, and products that often don’t work.

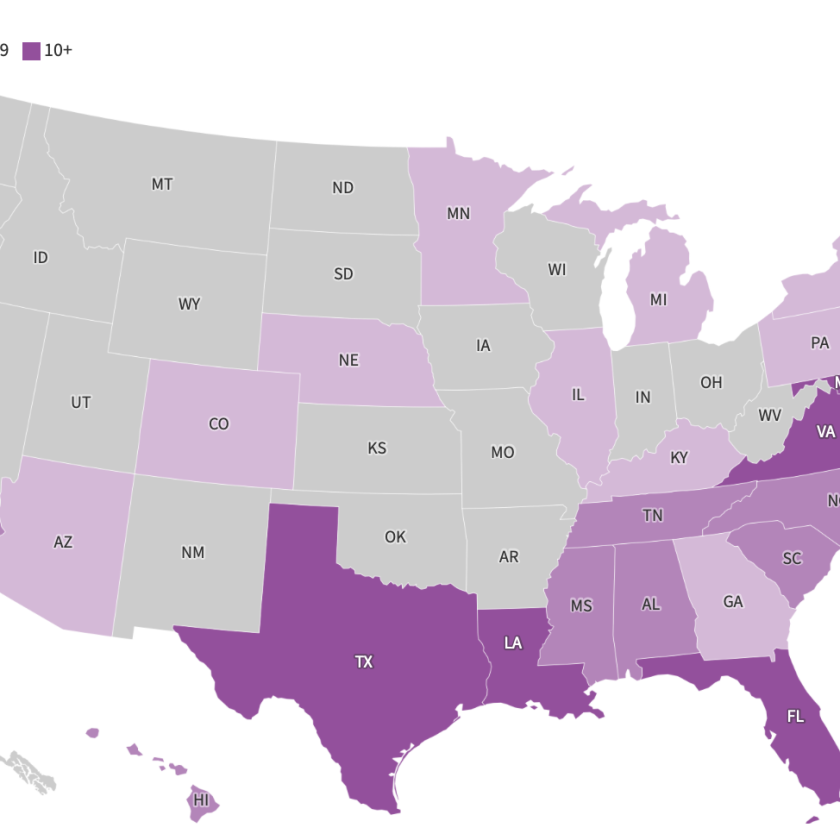

According to some estimates, Medicare alone spends at least $25 billion a year treating these wounds. But many widely used treatments aren’t supported by credible research. The wound care product business, worth at least an estimated $5 billion a year, booms while some products might prove little more effective than the proverbial snake oil. The vast majority of the studies are funded or conducted by companies that manufacture these products. At the same time, independent academic research is scant for a growing problem.

“It’s an amazingly crappy area in terms of the quality of research,” said Sean Tunis, who as chief medical officer for Medicare from 2002 to 2005 grappled with coverage decisions on wound care. “I don’t think they have anything that involves singing to wounds, but it wouldn’t shock me.”

“It’s an amazingly crappy area in terms of the quality of research,” said Sean Tunis, who as chief medical officer for Medicare from 2002 to 2005 grappled with coverage decisions on wound care. “I don’t think they have anything that involves singing to wounds, but it wouldn’t shock me.”

A 2016 review of treatment for diabetic foot ulcers found “few published studies were of high quality, and the majority were susceptible to bias.” The review team included William Jeffcoate, a professor with the department of diabetes and endocrinology at Nottingham University Hospitals Trust. Jeffcoate has overseen several reviews of the same treatment since 2006 and concluded that “the evidence to support many of the therapies that are in routine use is poor.”

A separate Health and Human Services review of 10,000 studies examining treatment of leg wounds known as venous ulcers found that only 60 of them met basic scientific standards. Of the 60, most were so shoddy that their results were unreliable.

read more at Philly.com