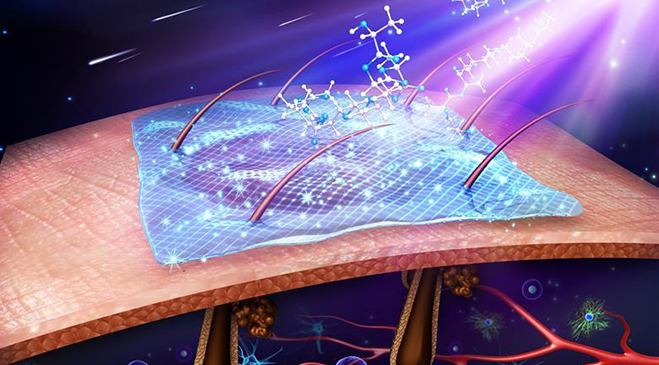

A new study has identified a peptide, derived from the Komodo dragon, called VK25, which can be synthesized and used as an antimicrobial peptide to promote wound healing.

The new research has identified (see below) a peptide found from the Komodo dragon (Varanus komodoensis), called VK25, which appears to be useful as a cationic antimicrobial peptide (CAMP). There is currently considerable interest in antimicrobial peptides in a world where antibiotic effectiveness is in decline. These peptides are potent, broad spectrum antibiotics which demonstrate potential as novel therapeutic agents.

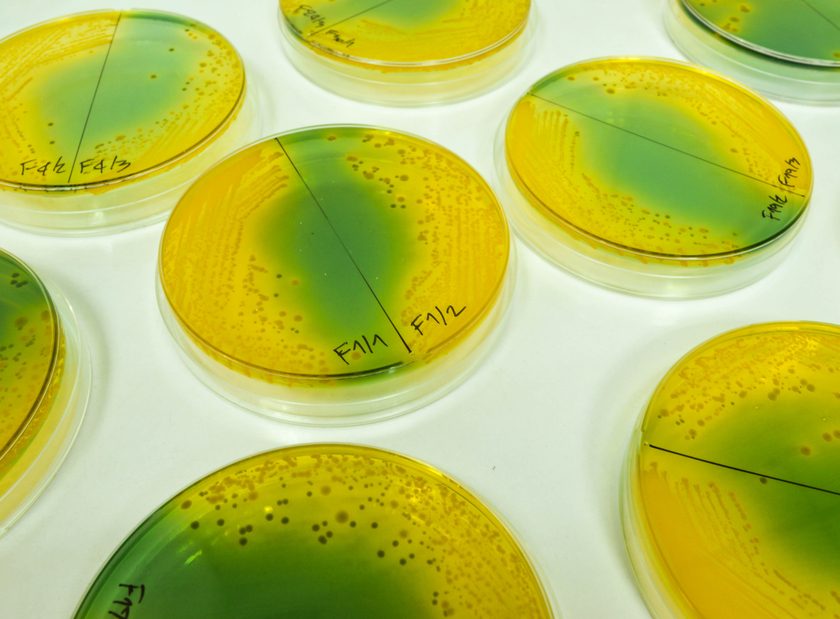

In trials the researchers (from George Mason University, Manassas, Virginia) have evaluated the antimicrobial and anti-biofilm activity of both peptides against a range of bacteria. A biofilm is a special community of bacteria that resemble a slime. Here the bacteria undergo physiological changes which makes them harder to kill, positing a risk in terms of wounds and with the process of healing wounds. The researchers, as Pharmaceutical Microbiology reports, undertook trial against two infectious bacteria called Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus (which, when some strains are resistant to certain drugs, becomes MRSA) .

The study results revealed that the synthetic DRGN-1 (rather than the ‘natural’ VK25) exhibited a potent antimicrobial and anti-biofilm activity. The protein broke through the bacterial membranes, bound to DNA, and killed the microbes, according to lead researcher Dr. van Hoek in an interview with the American Society for Microbiology.

The evaluation test was a scratch wound closure assay, which allowed the scientists to study the wound healing mechanism,. This showed the DRGN-1 peptide to be a strong candidate for development as an alternative to antibiotics. The next step in the research will be pre-clinical development, where the scientists will perform further testing, including testing the stability and safety of the peptide.

The findings are published in the Nature group journal Microbiomes and Biofilms, with the research article titled “Komodo dragon-inspired synthetic peptide DRGN-1 promotes wound-healing of a mixed-biofilm infected wound.”

Using this peptide as inspiration, scientists have designed a synthetic peptide, which, referencing the common name for the Komodo they have dubbed DRGN-1. This peptide contains two amino acids taken from the original protein sequence of the dragon’s VK25. The reason why researchers were studying the Komodo was to understand why saliva of these giant Indonesian lizards contains a host of bacteria yet the reptiles themselves do not become infected (which suggests an antimicrobial compound).

A bacteria-fighting compound, based on a molecule from Komodo dragon blood, helped wounds heal faster in mice.

In some myths, dragon’s blood is a toxic, vile substance. In others, it has magical properties, curing disease and making ordinary mortals invincible. When it comes to the blood of real-life Komodo dragons, both perspectives may contain a kernel of truth.

According to a paper published today in Biofilms and Microbiomes, a peptide that mimics a molecule found in dragon blood may slay bacteria, helping wounds heal faster.

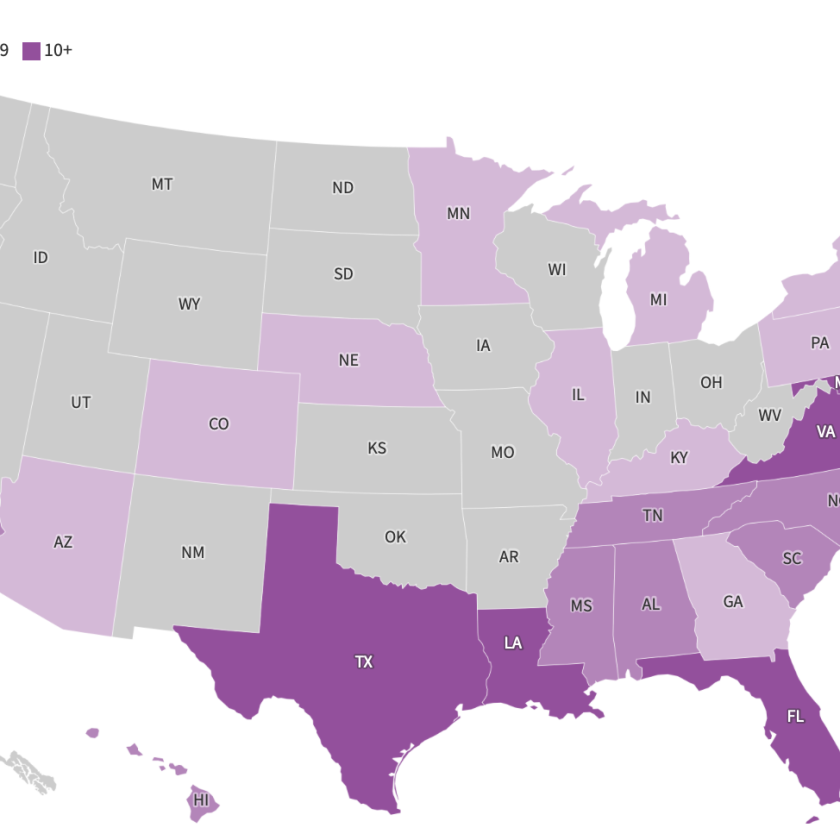

Researchers tested the compound in mice with skin lesions, and found the dragon-derived treatment helped the wounds close up faster. If the treatment proves successful in human trials, it may one day provide a new weapon in the battle against antibiotic-resistant bacteria, which are starting to become deadly, as well as biofilms—tough clumps of bacteria that are often impervious to antibiotics.

Chasing the dragon

Since 2009, Monique Van Hoek and Barney Bishop from George Mason University have been searching for new antimicrobial agents. Although their respective labs focus on bacteriology and biochemistry, they are also bioprospectors, searching for novel medicinal compounds in the blood of alligators and other ancient organisms.

This study started, as so many great adventures do, with a few tablespoons of Komodo dragon blood. The brave employees at the St. Augustine Alligator Farm and Zoological Park in Florida wrangled a dragon into a cage, so that a veterinarian could draw blood from near its tail—far away from its toxic mouth. (Van Hoek and Bishop emphasized that no Komodo dragons, which are endangered, were harmed during this experiment.)

Until recently, scientists thought Komodo dragons killed prey with the sheer power of their filthy mouths, giving their dinner a deadly bacterial infection by way of a bite. The notion was challenged in 2013, when researchers couldn’t identify any bacteria in a dragon’s mouth that would cause such a rapid and lethal infection. But, Bishop points out, that study was done in zoo animals, whereas wild dragons are probably exposed to more microbes. So the jury’s still out on whether Komodo dragons have the power to inflict insta-sepsis.