By Catherine E. Chung, PhD, RN, CNE, WCC

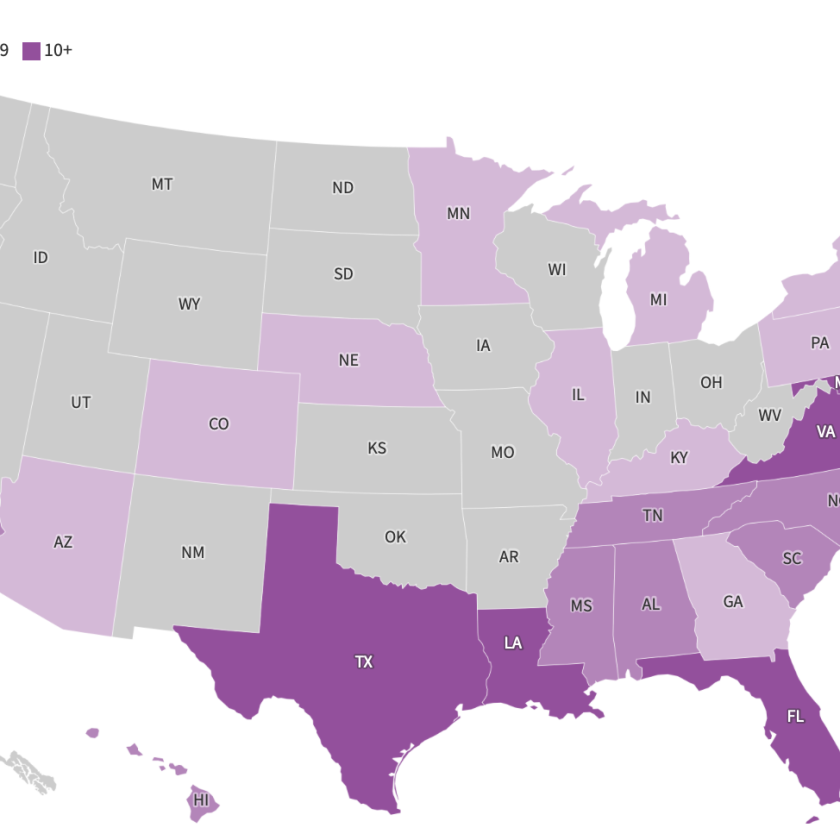

As a wound care clinician, you teach patients about medications, wound treatments, the plan of care, symptoms of complications, wound physiology—you teach a lot. And most patients probably smile and nod when you ask, “Do you understand?” However, health literacy research has shown that only 12% of the U.S. population is fluent in the language of health care. As health care has become increasingly complex, it has become increasingly difficult for patients to understand. Fortunately for your patient, you can translate.

Health literacy and your patient

According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, health literacy is “the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions.” Health literacy has little to do with someone’s ability to read or write. Rather, health literacy is about the person’s ability to acquire, understand the meaning, and appropriately use health information, which includes print material, verbal instructions, and online information.

Multiple factors affect health literacy, including physical status, age, culture, past experiences, emotional states, level of education, and socioeconomic status. Not every patient has the same ability to understand what you’re teaching. A patient doesn’t even maintain the same level of health literacy over time; for example, if a patient receives a devastating diagnosis, the associated emotional response will limit that person’s health literacy. Consider a man who went to a healthcare provider because of a wound he developed, but then learns he has diabetes. The news may feel overwhelming to him, with wound care taking a back seat to concern over the diagnosis of diabetes.

Health literacy is a concept that makes sense once clinicians, as the fluent healthcare linguists, consider it. Patients at highest risk for complications, including elderly patients and those of low socioeconomic status, have the lowest levels of health literacy. These are the patients most likely to feel intimidated about asking you questions because they see you as the expert.

For clinicians, who normally speak to other clinicians in their primary language of health care, lack of health literacy presents a challenge. For example, you’re treating an 82-year-old patient with diabetes and a traumatic lower leg wound that was infected and has been slowly healing. The patient asks when the wound will heal. You launch into a lengthy explanation of wound healing and the impact of blood glucose control, blood flow, the location and depth of the wound, and the treatment of choice. The patient replies, “But when will it heal?” The patient isn’t being difficult—he just didn’t understand anything you said.

To translate healthcare information so your patient understands it, you must determine the patient’s level of health literacy and meet the patient at his or her level of understanding. Here are some suggestions to help you start translating.

Assess the patient’s health literacy status

In addition to asking your patients questions about how often they have a dressing change or how their wound originated, ask why they think their dressing change is scheduled the way it is. Or, ask if they can see any difference in the wound and what they think that difference means. Listen not only to the words the patients are saying but also to the tone of voice they use: Do they sound certain? Confused? Anxious? Remember that negative emotions will make it more difficult for your patient to understand your teaching.

If new medications are prescribed for wound care, have the patient read the prescription label out loud. This isn’t a test for the patient—it’s an assessment technique for you. If the patient makes excuses not to read the label, this could be a sign of limited reading or visual ability, which will affect the patient’s ability to understand and perform wound care. This exercise will help you decide if the patient is proficient in the language of health care. Then you’ll know if you can translate at an introductory level or a more advanced level.

Use plain language

The Plain Writing Act of 2010 requires federal agencies to write all regulations in a clear and easily readable style. This is a good idea for wound care clinicians as well. It allows the patient to understand the teaching in simple layperson’s language. Examples of plain language include word substitutions, such as “follow” instead of “comply with” or “stop” instead of “discontinue.”

Healthcare terminology should also be converted to laypeople’s terms. For example, “purulent drainage” would be more meaningful to a patient as “greenish and smells bad.” Try to use words that are one or two syllables. For more tips for getting your message across, see More communication tips.

Limit information quantity

Just like students learning a foreign language, our patients can digest only limited amounts of healthcare language at one time. What constitutes too much information? That depends on your patients and how familiar they are with health care in general, how stressed they are about the wound and any associated diagnoses, how much support they have, and whether they’re concerned with the financial implications of the wound and associated diagnoses. So, as you can see, how much information you give your patient depends on your patient’s level of health literacy.

Try to break the information into logical steps that fit your patient’s needs. For example, you might teach the patient how to clean the wound during one appointment, how to pack the wound at the next appointment, and how to cover the wound at a third appointment if the patient seems very nervous about the process. Patients who previously have helped others with wounds or are calm about the process may be able to learn all the steps at once.

Verify information understanding

Don’t ask, “Do you understand?” It’s human nature to respond “Yes” to that question to avoid feeling inadequate. Instead, use the teach-back method. Ask the patient, “Could you explain back to me what we talked about? I want to make sure I told you everything I was supposed to today.” As the patient explains, you’ll be able to tell whether you successfully conveyed the information. You’ll also be able to determine if the patient can take in more information during the present appointment. If the patient can repeat only a small part of what you said, then you know to offer smaller chunks of information when teaching.

Your patients may not think of questions during your time together, but it’s likely they will think of them afterward. If you give patients permission to write down questions, they feel validated: The expert is saying it’s OK if they need more information later. This might seem silly, but many patients are afraid they’re wasting your time if they ask you questions about something you might not have discussed during their appointment.

Patient-centered care

As a wound care clinician, you want to practice patient-centered care. For your patients to be a partner in their care, they need to fully understand what is happening during their wound care and what to expect from the plan of care. After all, the translation your patient really wants to understand is the answer to “When will it heal?”

Selected references

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Simply Put: A Guide for Creating Easy-to-Understand Materials. 2009. www.cdc.gov/healthliteracy/pdf/simply_put.pdf

Evans M. Providers help patients address emotion, money, health literacy. Mod Healthc. Dec 9 2013;43(49):16-18.

Koh HK, Berwick DM, Clancy CM, et al. New federal policy initiatives to boost health literacy can help the nation move beyond the cycle of costly ‘crisis care.’ Health Aff (Millwood). Feb 2012;31(2): 434-443.

Osborne H. Health Literacy from A to Z: Practical Ways to Communicate Your Health Message. 2nd ed. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning; 2013.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. National Action Plan to Improve Health Literacy. 2010. www.health.gov/communication/hlactionplan/pdf/Health_Literacy_Action_Plan.pdf

Catherine E. Chung is an associate professor of nursing at National University in Henderson, Nevada.

DISCLAIMER: All clinical recommendations are intended to assist with determining the appropriate wound therapy for the patient. Responsibility for final decisions and actions related to care of specific patients shall remain the obligation of the institution, its staff, and the patients’ attending physicians. Nothing in this information shall be deemed to constitute the providing of medical care or the diagnosis of any medical condition. Individuals should contact their healthcare providers for medical-related information.